*

Konsentrasiekampe gedurende Anglo-Boere oorlog II is ‘n baba van die Engelse regering, maar hulle was nie alleen nie. Die Engelse regering EN al haar bondgenote, wat Afrikaners uit die Kaapkolonie daarby insluit, het die euwels op ons Boere volksgesinne van die bykans 20 Boere republieke afgedwing. Dit het gepaard gegaan met martelings, treiterings, gebrek aan voedsel en medikasie, ook verkragtings. Sommige Boer gesinne en families is totaal en al uitgewis sedert die Britte gebiede begin kolonialiseer het na 1806. Hul doelwit was grotendeels eerstens om die minerale regte in al die Boere republieke te bekom en te beheer. Tweendens was dit hul missie en agenda om ontslae te raak van die Boere volksgenote, identiteit, tradisies en geskiedenis. Daar is onthou word, daar is meer dan een blanke volk in Suid-Afrika net soos daar verskillende swart en bruin volke is.

*

Dit word na hoeveel dekades ontken dat dit nie volksmoorde is wat plaasgevind het nie. Vandag gaan dit steeds voort en het moorde en aanvalle nooit opgehou nie.

Konsentrasiekampe was 100% deel van die hele proses, waarin die Engelse regering met die hulp van haar bondgenote, oor die 30000 plase met voedsel vernietig het. Dit was ‘n totale heksejag wat Brittanje en haar bondgenote uitgevoer het op die handjievol Boere volksgenote Die Boere republieke was internasionaal erkende lande.

Daar word beweer dat die Engelse die swart volke ook in konsentrasiekampe geplaas het met net die basiese voedsel tot hul beskikking. Die konsentrasiekampe vir swartes was meerendeels uitgerig as arbeiderskampe en was dit nie dieselfde as dit waaraan die Boervroue, kinders en ou mense onderhewig was nie. Boere helkampe is deur die Britte beheer en gekontroleer, veral met gebrek aan voedsel en medikasie. Daar is nie veel bewyse van swart konsentrasiekampe of selfs die derduisende grafte nie

*

Uit Duits vertaal:

Jonas Kreienbaum het die artikel geskryf oor die koloniale konsentrasiekampe van Brittanje in die Boere republieke. Hierdie gebiede het slegs die Boere republieke geraak, waar die Boere gesinne verwyder is nadat meer as 30000 plase met voedsel afgebrand is deur die Engelse regering en haar bondgenote.

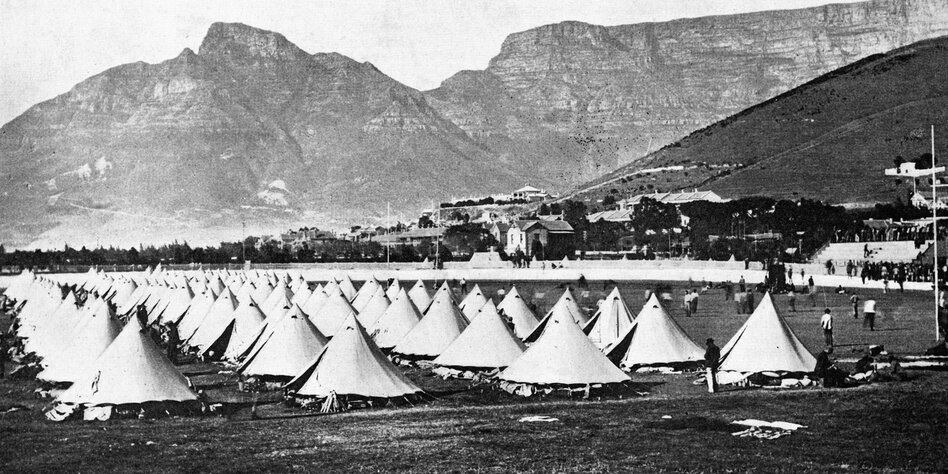

The concentration camp was an English invention, declared Adolf Hitler in the Berlin Sports Palace on January 30, 1940. “The idea was born in an English brain. We just looked it up in the dictionary and then copied it later.” The camps to which Hitler was referring were created during the South African War (1899–1902), with which Great Britain attempted to incorporate the independent Boer republics of the Transvaal and Orange Free State into the Empire integrate.

The British military had around 100 so-called concentration camps built in which they interned over 200,000 African and Boer civilians. In parts of colonial history research, which has been triggered in recent years not least by demands for compensation from the German state, another colonial example appears as a model for the National Socialist camps: the use of concentration camps in the German colony of South West Africa during the war against the Herero and Nama (1904–1908).

The six so-called prisoner kraals, which were built in the “protected area” on the instructions of Reich Chancellor Bernhard von Bülow, could be seen as forerunners of concentration camps such as Dachau or Buchenwald and – according to some historians – even as a model for pure extermination camps such as Treblinka. But how much did these turn-of-the-century colonial concentration camps actually have in common with the later Nazi camps? Was there a continuity of the camps “from Windhoek to Auschwitz”, as the Hamburg historian Jürgen Zimmerer put it?

At first the similarities seem obvious. In all cases, these were purpose-built, mostly fenced camps, all of which were called concentration camps at the time. In the soon overcrowded colonial camps, the internees lived in makeshift “native huts” or old tents, which often had to be placed in several layers on top of each other in order to provide any significant protection.

They suffered from being guarded “like oxen in a barbed wire fence,” as some Herero elders complained. And they suffered from a lack of clothing and food, which at times consisted only of flour and salt, and from inadequate medical care. Diseases broke out and the camps became “true valleys of despair,” as the Boer camp chaplain August Daniel Lückhoff put it. As was later the case in the Nazi camps, mass deaths soon occurred, claiming around 50,000 lives in South Africa and over 7,000 in German South West Africa.

Systematic devastation

But if you look more closely at the context and, above all, the purpose of the various storage systems, the clear picture disappears. The colonial camps emerged in the context of protracted wars that posed serious problems for the colonial powers. The Boers, descendants of European immigrants since the 17th century, soon fought the war in South Africa as guerrillas. They avoided open battles with the superior British troops, instead attacking isolated transport columns and then quickly disappearing again.

In order to make it more difficult for the mobile Boer commandos to operate, the British commanders Lord Roberts and later Lord Kitchener launched targeted attacks on the enemy’s supply system. The contested areas were systematically devastated, farms were burned down and all residents of these areas were deported and taken to the newly built, guarded concentration camps. The aim was to make it impossible for the Boer guerrillas to hide with sympathizing farmers, to obtain supplies or information, and ultimately to deprive the resistance of its base. The camps were therefore primarily a military means of ending a protracted colonial war.

This also applies to the camps in German South West Africa. Here the German commander-in-chief Lothar von Trotha waged the war against the Herero that broke out in January 1904 as a war of extermination, which is now viewed as genocide in large parts of research with valid arguments. This warfare was met with resistance in Berlin, among other things because it did not seem to bring about an effective end to the war. Reich Chancellor Bülow therefore ordered a change of course in December 1904 and, in doing so, suggested the establishment of “concentration camps for the temporary accommodation and maintenance of the remnants of the Herero people”.

The camps to which all captured Herero and later also Nama were brought were primarily intended to ensure that the “prisoners of war” would not escape and join the “insurgents” again. Through the effective “collection”, in which the Rhenish Missionary Society, which had been active in southern Africa since 1829, took an active part, and the internment of the opponents in camps, the de facto end of the war was to be achieved.

A comparable constellation cannot be found in the Nazi context. The Nazi concentration camps were created in 1933 not as a military means of ending a war, but as domestic political instruments to combat political opposition, which is a fundamental difference. It was only in the course of the Second World War, in the course of the enormous expansion and redesign of the Nazi camp system, that significant functional similarities to some colonial camps emerged.

From 1942 onwards, the SS Main Office for Economic Administration began to systematically rent out the camp prisoners as forced laborers, primarily to armaments companies. A comparable practice had emerged almost 40 years earlier in South West Africa. Here too, companies – and also private individuals – were able to hire interned Herero and Nama people as forced laborers for a rental fee. From 1905 onwards, large companies such as the Hamburg shipping company Woermann and the Stettin railway construction company Lenz & Co, which were active in the colony, even operated their own camps for their prisoners of war workers. These company camps are certainly reminiscent of the company-related satellite camps that characterized the National Socialist concentration camp system after 1942.

Death from forced labor

As in the Nazi camps, forced labor increased deaths in the camps in South West Africa. The German missionary Heinrich Vedder from Swakopmund wrote: “Sick people are few and far between because everything that can still move is driven to work and dies in the night.” Nevertheless, it would be wrong to talk about targeted “extermination through work” here. to go out. Unlike the Jewish concentration camp prisoners, who were only briefly exempt from direct murder in order to strengthen the war economy as forced laborers, but who were never meant to survive the war, the German colonial power also planned the interned Herero and Nama as workers for the post-war period .

The mass deaths in the colonial camps in South Africa and South West Africa were not the result of a targeted policy of extermination. The high death rates overall, probably over 40 percent in the German camps and up to 25 percent in the British camps, were the result of logistical problems with supplies, the disinterest of the military in charge in prisoner issues, a lack of knowledge about diseases such as measles and scurvy and the desire the labor exploitation of the internees. To imagine that the extermination camp was invented in southern Africa ignores the historical reality.

There was no equivalent in the colonial context to Treblinka or Belzec, whose sole function was to kill practically everyone who arrived within a few hours. With a view to the fundamental functional differences between the British camps in South Africa and the Nazi concentration camps, the question arises as to what influence Hitler, Himmler or Theodor Eicke, who, as the first head of the concentration camp inspection, had on the design of the Nazi concentration camp system actually should have copied from the British. Hitler’s reference to simply copying an English idea is nothing more than a propaganda maneuver in the course of the war against England.

But the German camp experiences in South West Africa could hardly serve as a model. Firstly, here too, with the exception of the hiring of forced labor, the functional differences clearly predominated. Secondly, unlike the British camps, the German camps on what is now Namibia hardly made it into the European press and were largely forgotten by the 1930s. And thirdly, there is no evidence that the few people who, like Franz Xaver Ritter von Epp, had personal experience in South West Africa and later played a role in Nazi Germany, propagated the establishment of concentration camps. As Reich Governor in Bavaria in 1933/34, Epp opposed the expansion of the camp system controlled by Himmler.

If one takes into account the fact that former colonial actors played no role in the design of the Nazi camps, that the German colonial camp experience in the “Third Reich” was largely forgotten, and that colonial and National Socialist concentration camps differed greatly from one another in key points, a continuity of African concentration camps appears unlikely after Auschwitz.

https://taz.de/Konzentrationslager-im-Kolonialismus/!5212447/

*

READ – LEES

RELATED INFORMATION – VERWANTE INLIGTING

Anglo-Boere oorloë – Springfontein

Anglo Boere oorloë – Shepstone

British concentration camps – ABW (Rudie Rousseau)

ABW concentration camps – Rudie Rousseau ea

Concentration camps by the British empire

Verskroeide aarde – Scorched earth

1900 Dertig sikkels silwer (30000 Britse pond) – ABO

Britse konsentrasiekampe Hester de Beer

British horses during the Anglo-Boer wars

Shepstone – Natal, roots of segregation

Commonwealth and suppression by British Colonialism

Jan Smuts – Churchill – Rhodes – apartheid : British rules

*

Contact Admin:

Admin kan gekontak word by

volksvryheid9@gmail.com

[…] Konsentrasiekampe tydens ABO […]

LikeLike

[…] Konsentrasiekampe tydens ABO […]

LikeLike

[…] Geen of min voedsel en mediese voorraad is weerhou. Met voorbedagte rade om totale uitwissing in die oë te staar. Dit is eenvoudig barbaars en onmenslik wreed wat die Britte op ons Boere voorsate losgelaat het. Vrouens en kinders is soos diere aangejaag en soms in oop trokke vervoer sonder sanitêre geriewe. Daar was nie altyd tente om in te woon nie, maar was blootgestel aan al die elemente, koue, sneeu, reen, hael en wind. Toilette was daar ook nie, ook nie in die veld of op treine nie. Britse konsentrasiekampe Hester de BeerKonsentrasiekampe ABO Konsentrasiekampe tydens ABO […]

LikeLike

[…] verklaring – Jan SmutsKonsentrasiekampe ABOKonsentrasiekampe tydens ABOAnglo-Boer War and soldiersAnglo-Boere oorloë SpringfonteinGrondgebiede van Boere […]

LikeLike

[…] Konsentrasiekampe tydens ABO […]

LikeLike

[…] Oorlog: KonsentrasiekampeBritse konsentrasiekampe Hester de BeerKonsentrasiekampe – ABOKonsentrasiekampe tydens ABOAnglo-Boer War and […]

LikeLike

[…] en die XhosaSlag van Stormberg – 10 Desember 1899Die berge – RetiefklipKonsentrasiekampe tydens ABOKonsentrasiekampe – […]

LikeLike

[…] Konsentrasiekampe tydens ABO Konsentrasiekampe – ABO […]

LikeLike